|

|

As we know, semiotics can translate a picture from an image into words. Visual communication terms and theories come from linguistics, the study of language, and from semiotics, the science of signs. Signs take the form of words, images, sounds, odors, flavors, acts or objects, but such things have no natural meaning and become signs only when we provide them with meaning.

Pictorial semiotics is often concerned with the study of pictures into a more constructive verbal description, while maintaining confidence in the objectivity of the practice. A linguistic community that speaks the same language is a group of people making verbal agreements, speaking similarly as long the community lasts. In these terms we have to read the work of Thompson and Laubscher.

Through the study by Dan Cameron, we already explained that Kentridge stands out as an artist struggling with the past in the face of the present. Perhaps more than any other, the descriptive ‘introspective art’ applies to Kentridge, who remarks that:

[T] here may be a vague sense of what you’re going to draw but things occur during the process that may modify, consolidate or shed doubt on what you know. So drawing is a testing of ideas, a slow-motion version of thought. [. . . ] The uncertain and imprecise way of constructing a drawing is sometimes a model of how to construct meaning. What ends in clarity does not begin that way.

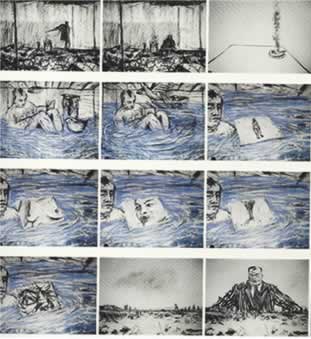

Thompson and Laubscher examine Drawings for Projection as a written description on violence and its reparation, indicating three thematic responses: violence as erasure, re-membering, and the face of the other.

A - The paper starts with the first thematic identifying several sites of violence portrayed in all the films, some easily recognizable (bombs, explicit violent acts, killings), others more subtle like the violence portraying the inhumane anonymity (symbolized in the series by the constant presence of obsolescent objects and outdated technologies and economies such as old-style telephones, typewriters, and ticker tape machines), and as a consequence of the ideological, as for example in Felix in Exile (1994). According to Thompson and Laubscher, the importance is the reading in terms of erasure: like in the violence of murder and killing, even in the banishment of exile; the desire is for the other to literally disappear.

B - The second response is called re-membering: if violence erases the other, the restorative or healing injunction involves a resolute, courageous, and undaunted willingness to revisit the sites and landscapes of violence. Kentridge does not want us to defend against feeling through mindless repetition or mere mimesis, but to re-member actively and affectively. The effect is an ethical call to conscience.

C - The third response, defined as the face of the other, remind us that violence involves the other, needs the other. Kentridge animates this injunction by threading symbols of the fecund and the ethical throughout the series. He includes the images of the fish, water, and the feminine as correctives and ethical counters to violence — for example, in Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989), Sobriety, Obesity and Growing old (1991), Felix in Exile (1994), Weighing . . . and Wanting (1998), Stereoscope (1999). Water is associated with the feminine and the fish, and represents fecundity, fertility, and saving grace in terms of ethical possibilities of relatedness, the capacity to engage in dialogue, and being humane. On Water, Kentridge said:

I had never had a specific idea of water being cleansing. I just have a sense of wanting of that water, and welcoming it when it appears in the drawing. This is not a theme, but a recurrent image, a feeling that does go through my drawing. A longing for water, for buckets being poured over people.

Thomson and Laubscher argue that healing violent trauma and reconstituting the self and its relationship to, and with, others involves a courageous circling between re-membering such that we recognize the face of the other, and the ethical nature and responsibility that accrue from such recognition.

The strong counter-pull towards violence occurs through the erasure of the other’s profoundly humane and human presence. The restorative and healing responses to violence, particularly that of apartheid, have to be informed by a profoundly ethical acknowledgment of the other. This injunction operates as both cultural and personal therapy, and has salience at the level of the group in politics and policy, for example, as well as the self in terms of psychology and psychotherapy.

Kentridge’s project insists on the re-membering of atrocities, our personal and shared responsibilities for South African political violence, and the necessity of our taking note of its presentation. The time, the change, the presence and absence are central themes in the work of William Kentridge, issues that are metaphorically in the process of continuous succession between erasure and drawing.

In Felix in Exile (1994), for example, the context in which the story takes place is South Africa's apartheid. Kentridge chose a series of symbols and figures that recur in all his videos of this period: the African woman, Soho, the middle-aged businessman, Felix, an alter ego of the artist himself, the African landscape, the factory smoke, African songs, the water, the fish and the mirror.

Thomson and Laubscher support the idea that the characters represented are living inner battles and policies that reflect the situation and life in South Africa during the years of racial separation. But at the same time, the stories reveal elements represented symbolic of universal opening a space for reflection on issues such as death, the existential loneliness, love or the timeless grandeur of nature. The items shown arising from the imaginary poetic inner artist, but manage to transcend the subjectivity becoming emotional baggage and universally understood language.

All figures and the elements are in constant flux: bodies turn into landscapes, animals become objects, and everything seems to live a continuous transformation.

The unfolding of the animations spread in structures similar to those that the brain produces immediately before sleeping, when images emerge from the memory in seemingly unrelated sequences and blend briefly and then disappear again.

Vanessa Thompson and Laswin Laubscher, “Violence, re-membering, and healing: a textual reading of Drawings for Projection by William Kentridge,” 2006, South African Journal of Psychology, 813.